By Malek Mneimne, Ph.D.

“What is real? How do you define real? If real is what you can feel, smell, taste, see and hear, then ‘real’ is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain.” – Morpheus, The Matrix.

“I don’t even remember what I did yesterday.” – Anonymous.

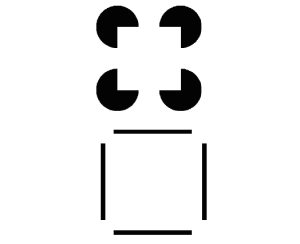

Like The Matrix, many movies and books portray objective reality, or some aspects of it, as illusory; that is, not ‘real.’ Because the more ‘extreme’ variants of this idea do not lend themselves readily to empirical investigation, can probably only be discovered (as in The Matrix and The Truman Show), and we do not currently have evidence for them, they are most likely purely hypothetical. However, studies conducted by psychologists support a more basic variant of this idea, that at least some parts of reality might be partly illusory. Psychologists define perception and memory, in part, as constructive and re-constructive processes, which do not always accurately represent or re-represent objective reality, respectively. For example, what do you see in the images below?

In studies using these kinds of ambiguous stimuli, many people have reported seeing squares (or other stimuli) in the images that were not actually present. Every day, we are faced with these, and similar kinds, of ambiguous stimuli that our brain resolves by drawing inferences. These inferences, however, tend to be colored by past learning experiences, cultural beliefs and values, biological and evolutionary dispositions, and social and emotional influences. Both illusions and a related, but more extreme variant, hallucinations, illustrate how the present perception of ambiguous stimuli is influenced by a multitude of factors, which in some cases biases people to perceive something that is (a little) different from what is actually present. Therefore, on the basis of these and multiple similar findings, perception is often considered a constructive process, which does not always accurately represent reality.

If you think of perception and memory as falling along a sequential, linear continuum of cognitive processes, with perception occurring first and memory later on in the sequence, then it will probably be no surprise that if perception can be inaccurate, then so too can memory. In 1932, Frederic Bartlett, a British psychologist, gave participants a Native American folk tale to read and memorize. When he tested their memory for this folk tale minutes, weeks, and months later, he found that, over time, participants gradually replaced unusual events in the tale with events consistent with their own native British culture. In another study, 30% of undergraduate students exposed to a graduate student’s office for several minutes later remembered seeing books when there were none. Studies such as these suggest that people often remember events, not exactly as they happened, but partly in line with previous experiences they’ve had in similar situations. Like perception, memory also tends to be colored by past learning experiences, cultural beliefs and values, biological and evolutionary dispositions, and social and emotional influences Therefore, on the basis of these and multiple, similar findings, memory is often considered a re-constructive process, which does not always accurately re-represent reality.

Whereas these kinds of perceptual inaccuracies are often intriguing and relatively inconsequential at individual and societal levels, memory inaccuracies can have relatively significant consequences at both levels. For example, a well-known cognitive psychologist was once arrested, forced to pose in a witness line-up, and identified as the perpetrator of a rape. Ironically, however, at the time of the crime, he was on a television program discussing methods for improving facial memory. Moreover, roughly 20% of witnesses selected in line-ups are not the actual perpetrators. Although reports of recovered memories often contain events that actually took place and studies suggest that memories can be suppressed and/or inhibited for periods of time, in other cases, individuals have been arrested and/or sued on the basis of “recovered memories” of abuse even though evidence later revealed that they had nothing to do with the accusation. Research also suggests that memories can be falsely implanted, implied, and/or distorted. Indeed, some psychologists argue that Dissociative Identity Disorder (formerly Multiple Personality Disorder), which has almost always involved reported cases of early trauma, involves leading questions posed by a therapist that imply the possible existence of “repressed abuse” and/or “multiple personalities” and suggestibility on the part of the patient.

Another potential problem with memory inaccuracies pertains to prediction and emotion. When it comes to predicting what will (or should in irrational cases) most likely occur in a given situation, people often base their predictions upon memories. As such, it seems plausible that some of the more distorted and maladaptive expectations and beliefs that people have derive, in part, from inaccurate or distorted memories (as well as, in part, from ‘over-prediction’ of “what will likely happen” to “what should happen” instead). For example, imagine playing a baseball game and hitting the winning home run. At first, it is unclear whether the ball would clear the fence or not, but as you round first base, it makes it into the first row of bleachers just over the reach of the outfielder’s glove. Days later, you recall the incident to a friend, noting “I smashed that ball! You should’ve seen it!” “Smash” in this context may be a matter of perspective, but can also imply that not only was the hit a homerun, but that it almost went out of the stadium. As suggested by research, each time this story is told, is it is also modified in one’s memory. During the next season, you may be upset because you haven’t smashed any other homeruns despite your prediction that you should.

Unfortunately, there is no way to determine the accuracy of a person’s memories with 100% certainty. Essentially, REBT helps people identify ways for coping with irrational expectations and/or beliefs that may stem from such memories. REBT theory does not propose ascertaining the validity of or disputing memories, however. Therefore, based upon this analysis of the influence of memory inaccuracies in emotional disturbance, “lapses” in rationality or slow progress , particularly during the initial sessions of REBT, with the original inaccurate or distorted memories largely unchanged, would not be surprising. Although one may learn during the initial sessions from their REBT-trained therapist that it is illogical to expect a homerun on every at-bat, their (unconscious) brain may still retrieve the original inaccurate memory at the sensation of associated baseball stimuli (e.g., seeing a bat, helmet, baseball stadium, hearing the crack of a bat connecting with a pitch), along with the original irrational belief that “I should be able to hit a homerun every time I step to the plate.” This could explain, in part, why repeated rehearsal of alternative, rational beliefs (e.g., “I’d like to hit a homerun every time I step to the plate, but there is no reason that I have to.”) in the presence of associated stimuli is important and why it may take time before rational responding in similar situations becomes relatively automatic and “lapses” in those situations decrease.

Not awful, just annoying.